Adelaide Damoah in Conversation with Eugene Ankomah

Born in 1978 in the UK, Eugene Ankomah has already had an impressive art career spanning 18 years. Ankomah’s family settled in the UK when he was 13 years old. His love affair with art started at the tender age of five when he was first given the task of copying the image of a monkey at school. Described as a child prodigy even then, Ankomah went on to impress his school teachers enough to make his first sale while at the age of 16 and to win a number of awards and prizes which would later form the basis for his blossoming career. Ankomah kindly took some time out of his busy schedule, which also includes working with young people in art, to discuss his career to date and his thoughts on success in the art world.

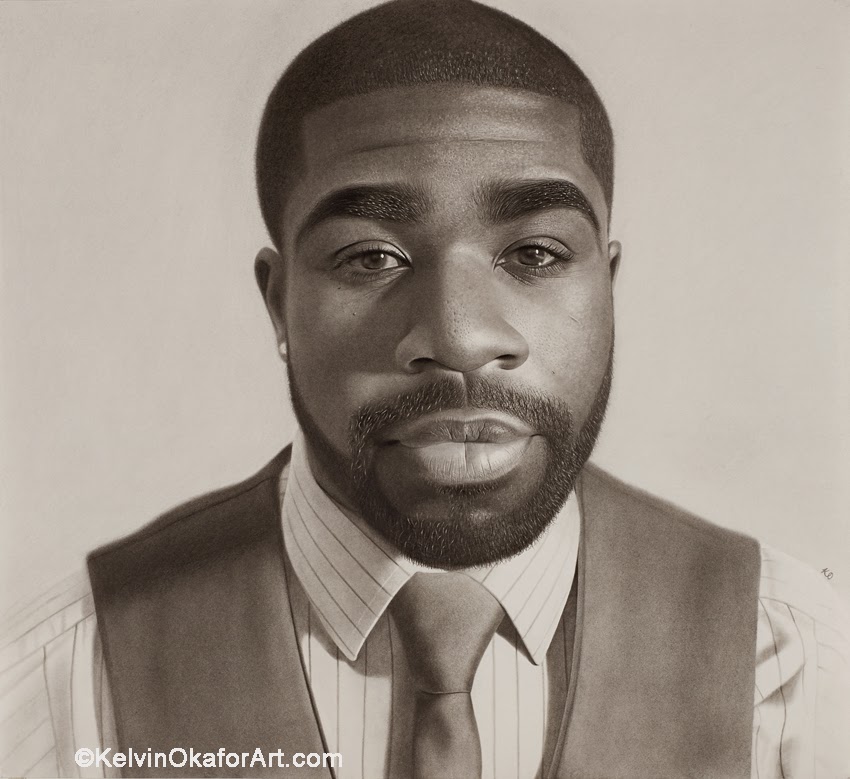

|

| Something Inside So strong. 2012 |

AD: I see a lot of African symbolism in your work. Would you say that your life growing up in Ghana influences your work?

EA: Most definitely yes! Watching all of those dramas on TV and seeing the cultural references that were made by a lot of the characters got me intrigued from an early age- but funnily enough, I did not really show any of it in my work. It was a bit later when I was tying to find a part of my identity through my art, when it occurred to me that there was no stronger way to communicate where I was from than to put a bit of my background into the work. I felt that it was all connected.

AD: What did you study at Central St Martins?

EA: I did a foundation in Fine Art at St Martins.

AD: And then you went on to Westminister university?

EA: Yes.

AD: And what did you study there?

EA: It was illustration. But it was one of those courses where you could express yourself in so many different ways. There were people doing painting, ceramics, sculpture.. All sorts of different things, you know, mixed media… And that to me was just perfect because I did not just want to stick to just one thing and be a painter. But it did give me a chance to develop painting, print making and all sorts.

AD: At what point did you decide to go ahead and become a professional artist?

EA: I don’t think I ever decided to become an artist. It was so natural for me from the very beginning. I have never felt like it was a conscious decision. It was as if I had no choice… But I would say that I noticed that I was good at it at about the age of five. The reason I say that is because back in Ghana, I remember a teacher giving us these books with lots of imagery inside. Our task was to choose an image and copy it. At that time, I used to go to the house of a man who had a monkey. I would play with the monkey- so I went straight for the image of the monkey in the book the teacher gave us. I remember that the monkey was in a tree, so I copied the image and I added something to it which I had seen in real life with my monkey friend. It was a chain which was tied to the waist of the monkey and then connected to the tree. The teacher came around, looked at it and was really surprised that I had not only drawn it very well, but that I had also added something to it. I remember a few of the kids coming around to my table and having a look and being very surprised. That was when I thought that I was good at drawing. But I also used to draw stuff at home. My mum would give me paper and I would just sit down passing the time drawing all sorts of things. It has just been a journey from that time that I have never stopped.

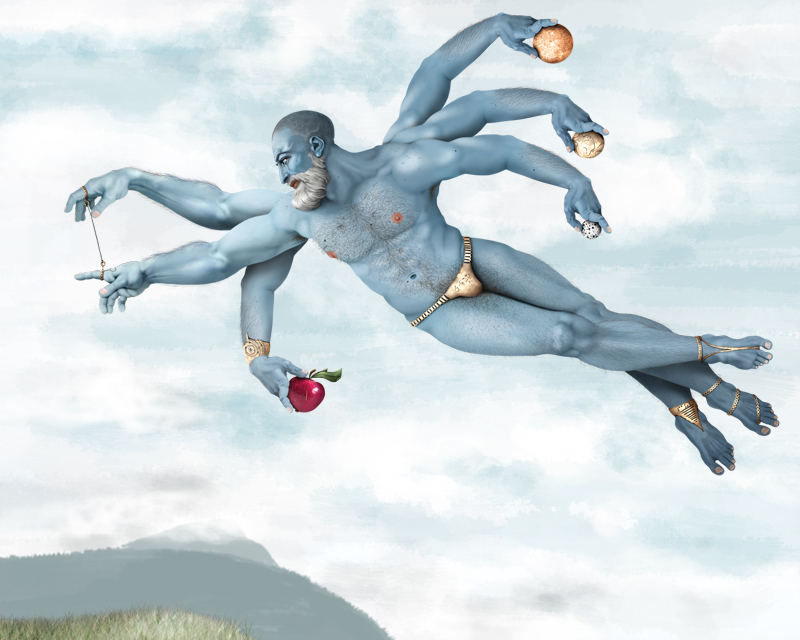

|

| Young Daniel. Spray paint, vase and blackened water. 2012 |

AD: Are you now a full time artist?

EA: Yes I am. I do some other work on the side, but it is all art related.

AD: Excellent. What are some of the other things that you do? You mentioned a project where you are working with young people.

EA: I have been offered projects where I work with young people. It has always been a joy for me, working with young people to be honest. I feel that strong desire to impact their lives. To give something back- to teach them, or to help guide them… To just sort of work together. I have learned a lot from them as well so it is a nice thing to do. I have also had a couple of stints doing artist residencies.

AD: At what point did things start to take off for you after you graduated?

EA: It started to take off when I was 16. Because just like when I was at primary school, I became the person to go to when you needed something to be drawn. After about a year of continuing to draw for other people at school, a teacher approached me and insisted that I do A level art with him. I continued art to A level and when I was 17, I was nominated for a prestigious award called the Peter Evans award. Within a week of entering, I was told I had won £150, which was a huge deal to me at the time. That was when it quickly spread throughout the school. The local press came in, took photographs and did a short interview. From that point, a lot of the work I had made was used for the school brochure and teachers hand books. Everything progressed from there…

AD: Would you say you started making a living from your art straight after graduation from university or was there a latency period?

EA: I was lucky in the sense that right after secondary school, I already started having requests from people who wanted portraits. I also had a couple of commissions from my local council to design some posters, post cards and a couple of paintings here and there. It sort of kicked off from then, but it wasn’t consistent.

AD: So it continued and I imagine it snowballed after you left university?

EA: Yes it did. By the time I graduated, I had already participated in a few competitions and had started showing my work from the age of around 16 or 17 at a local gallery. I remember entering a painting by the title of tree into a competition- which you could interpret how you wanted- and I won the second prize. I just kept working hard really and looking for opportunities to show work in as many places as I could.

AD: At what age did you have your very first solo show?

EA: I was 16 or 17. I was still at school. It was arranged by my art teacher at school.

AD: And where did you have that?

EA: In the school in Willesden Green, London.

AD: Did you manage to sell any work there?

EA: No one bought anything at the show, but I did get two commissions for portraits out of it, so it lead to something.

AD: Do you remember when you made your very first sale?

EA: I think I was around 16 and still at school. It was a small drawing I had done which one of my teachers really liked. I did it during one of the lessons when a teacher did not turn up. I remember that my teacher said that if he saw it in a gallery, he would buy it straight away. He later asked me to sell it to him, so I did. Gosh, it is funny, you are bringing back memories!

AD: How much did you sell it to him for?

EA: I think it was around £40.

AD: Well done! I am going to get a little bit political here. I came into the art world pretty late, around 2006. My experience of it so far is partly that it is run by upper middle class white men, which obviously they naturally have their own preferences in terms of what and who they wish to promote. What that means for minorities is that sometimes we get overlooked. As a result, very few minorities have been validated by the establishment. As a black British artist, is that something that concerns you?

EA: Yes, I mean obviously I am starkly aware of it. It is something you can not avoid and I think if you fall into our category, you will have experienced it in one way or another, without a shadow of a doubt. But one of the things that I have always done is to just not pay any attention to the sort of tricks and things they do- lets just leave it at that. One of the things that I learned early on, which I think is a very powerful thing is that galleries obviously exist to sell to the public. So I realised that if my work was shown to the public by my own means- whether it was shown in a local library or a church or whatever, that I could show to the very people that the galleries target. So the moment I started getting attention from the wider community, I focused on exposing my work to them at every single opportunity I had, even if it was something I had designed for someone. So I have always been aware of the politics and things that you are talking about. But I just focus on finding my own means to put the work out there and just focus my energy on unusual ways of getting people to see and buy my work. I have a by any means necessary type of attitude.

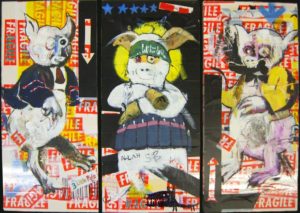

|

| Three Little Pigs. Tryptich |

AD: It sounds like to an extent, you are creating your own market, rather than trying to rely on an already existing establishment to do it for you.

EA: Exactly. I think that is very similar to what the graffiti artists do. They put the work out there and the public gets to see it and they make their name without a gallery and then galleries all of a sudden become interested. They become popular and people talk about them, then they are suddenly desirable aren’t they- which is complete nonsense! It really is. Its so hypocritical.

AD: Western art world experts have discussed at great length a shift towards African art becoming more desirable. This shift in art world thinking seems to me to be almost palpable, especially with the 2013 African art exhibition at the Tate, the 1:54 Contemporary African Art Fair in London and the 2013 Turner prize nomination for London based Ghanaian artist Lynette Yiadom-Boakye. How do you think this shift will affect African artists going forward, including yourself?

EA: In my opinion, African Art has always been super desirable, especially looking back to just before the advent of Cubism and so forth. But it has somehow been seen as a lesser art form. Although fashion in art and tastes have changed and moved back and forth towards African Art, I think world cultural developments, including that in music, namely Hip pop, rap and High Life have obviously reached a point where African culture cannot be ignored any longer, as its so strong and powerful. Equally African art and its artists have been gathering pace and no longer can it be seen as “African Art”, but simply art! however, I still feel African artists have to contribute something new, and something that has a fresh take on the world, or work with a distinctively strong voice for them to be taken seriously. In fact, I think it has to teach the world about our culture, so the audience and collectors get to learn something new from it. For me the attention and respect, will hopefully mean that certain doors are not still closed when I knock on them.

AD: You have won a number of awards and I read that you have also been compared to Yinka Shonibare and Chris Offilli- which is pretty good as far as comparisons go! Bearing in mind everything that you have achieved to date, what would you say was your definition of success in the art world?

EA: I think for me, first and foremost it was about getting as many people to see the work as possible. Getting into the position where I could share my work with people. I realised that when people saw the work, a lot of people were affected in one way or another. That gave me so much joy and it meant that I was allowing people to think and feel in a different way through the work. On a personal level, that was my first definition of success. It progressed from there to wanting to sell to people. So those two things… First and foremost, it is about just getting people to see it, because whether your work sells or not, it is a great confidence booster. Doing that allows you also to establish your own objectives before people start trying to make them for you.

AD: So the sense of joy that you get from showing your work to people…

EA: That’s it. How it affects them, how they enjoy it, the feedback, how it allows them to think and feel differently, I think that is just brilliant.

AD: By your definition, would you consider yourself to be a successful artist at this point?

EA: In that case, most definitely yes.

AD: have you ever experienced being a “starving artist?” If so, how did you get past it?

EA: I think that the whole idea of the starving artist is blown out of proportion. But I do think that it does exist. But there is something really strange about it for me because I think that the public do seem to enjoy the idea of the starving artist because it seems so mythical and romantic. Its just a bit ridiculous really and so I do think that it exists. I think that many artists do go through patches where they are either starting off so nobody buys your work or nobody knows you and I think we live in modern times where you can get some other job to help sustain you financially. I have personally gone through moments, especially in my early days when I would make lots of work and nobody wanted to buy it. You do go through those patches but I think it is important for artists not to fall into the trap of believing in that sort of thing because I think it is so important to think success before success actually happens. So I just don’t like that concept at all the starving artist, but of course, I know that it does exist but I think that there are always ways around it.

AD: What would you say is your ultimate dream for your work?

EA: I know a lot about art history and I have studied a lot of artists since I was young and I know what has been created. I am hyper aware of what is possible. If the history of art could be pushed into a circle, I am aware of what exists outside of that circle. So I have very strong ideas in terms of things I want to create which have not been done yet, or have not been stretched as far as I think they could be stretched. I have this idea that I have to create these things but one thing that is very important to me is the idea of reinvention and the ability to come up with different things which are all equally an expression of me and something which reflects my changes as I grow older. That has to be one of my ultimate goals. I have various ways of expressing myself in that regard- showing itself in a variety of types of work. Some people may look at what I am doing now or what I may do in two years time or even in a couple of months time and wonder if they are looking at the work of the same person. But it is important for me to do that because it is important for me to reflect on things. But that is my ultimate goal, to be able to fully express the things that I have in my mind and to just create and do whatever I want.

AD: You mentioned your knowledge of art history. Where do you see yourself slotting into art history? How would you define yourself?

EA: OK, there is a popular young British artist who is a friend of mine. He was looking at my earlier work a couple of years ago up until a certain point. He looked at the work and said, “Looking at your work is almost like looking back on the whole history of art. It is almost like going backwards.”

What he meant was that because I was so hungry as a young artist to experiment, learn and grab from as many artists and movements as I wanted, I completed a number of different works which reflected the ideas of many different artists and movements throughout history. This means that when you look at my work, you see so many different influences coming from so many different directions. For me, I think it is a positive thing that I started that way. I am glad that people can see that. I also like the idea that I have taken what I can from these people and these movements and reshaped it in a different way. So I hope that I can be seen as a person who has contributed after having taken and learned from all of these people. And as I said earlier, I have very strong ideas in terms of where I want to go with it and the things I want to create in the near future which will hopefully have that stamp on it because I think art is so free that you can really do whatever you want.

AD: Can you tell me a bit more about some of the ideas you have and what you have got coming up?

EA: One of the things I created in 2011 which was will be introduced soon hopefully is a project called the blacked out portrait. Blacked out meaning, you know when you have “lights off” in Ghana- that sort of blacked out. About a year before the riots of 2012, I noticed that the young people I was doing projects with had a certain suppressed thing about them. I think it was due to society putting a lot of pressure on them. So I started experimenting with these blacked out portraits where all you see is the eyes of the young person, but you don’t see the mouth and you don’t see the features, so they are expressionless. But at the same time, there is something quite intimidating about them because a lot of them are wearing hoods. Despite the lack of expression, it is very expressive and it has a very urban street look about them. So that is what those works are about and those will be introduced hopefully at the end of 2012.

|

| Ankomah as Young Hoodie Character. 2012 |

Another thing I have been working on is a book called Play. It will be released hopefully near November or December of 2012. The Play book is about how men perceive women. The chase of a man going after a woman and all of the things that go with that. It is a picture book. So from the very front to the back cover, it is made from my original art. It is influenced by movies. That sounds a bit confusing so I will break it down. When you are watvching a DVD, you get a subtitle in the menu, you have that at the front of the book and then as you go through the book, you have other references and other imagery and symbols we relate to watching a DVD and remote controls. It could be the rewind button, the play button, all that sort of stuff. They are all used throughout the book. So at certain parts you are asked to pause. At certain parts, you are asked to fast forward. But from the cover to the end, you have all these things, this imagery, which is very expressive. I am very excited about it because everyone who has seen it has given me very positive reviews and feedback.

|

| A Step Too Far. 2012 |

AD: Is this a photographic book? Or is it hand made?

EA: I made it with my hands. It is painted mostly- and sort of mixed media. The book will be reprinted and then sold in copies as limited editions.

AD: But the original book is just a one off piece.

EA: That is it. So everything will obviously come from that. Another thing I have is a film that I have just made. I completed it a couple of months ago now and it is called the Wake Keeping. It is a 16 minute video or short film which I have made with a producer called Pete Further. It is in post production at the moment and we have not decided when it will be released. I play myself with the top hat and everything else, like a spiritual character who is there to protect a woman in the video.

There is another video which I have been working on with a video maker called Ruth Dupree called the Hatters Reality, referring to me. The Hatters Reality is more or less about my journey as an artist. So in a sense, it is a bit like the interview we are doing now and the stories I am telling you, but imagine that expressed through video… But expressed in a way that it is not so literal, it is more abstract and you see me putting on my face paint and close up shots of how I do it and then I speak in Twi and it is interpreted in English and then I speak in English and you get a Twi subtitle. I talk about my experiences in Ghana, you know, like the question you asked earlier about how my life in Ghana influenced what I do now and my vision of being an artist and what I do with my work now and the meaning behind how I dress up and how I paint my paint and all those performance things I do. It has already been screened.

AD: Where will you release them? Will there be a screening or event that people can go to?

EA: There will be a screening. Possibly in South London at a small cinema. But all of this information will be on my website a little bit later once we have decide exactly what we are doing with it.

|

| Acene from “Wake Keeping” 2012 |

AD: Could you tell me a bit more about your persona with the top hat and the face paint?

EA: From my early days as an artist, I realised that I could think in a different way. So for me the dressing up and performance thing is just another aspect of what I do. I would say that the top hat and the makeup is a mixture of something European and African. Not necessarily Ghanaian, just African. So it is like combining a cultural heritage with the idea of me having been born in England and the idea of the gentleman. So it is a mixture of the 18th century gentleman with an urban twist. But I am conscious that as a person, I am a bit bored with mens fashion. I think mens fashion is pretty boring in comparison to what you women have! Seriously. I say this to people all the time, so it is a way for me to challenge what is possible in terms of what we can wear and what we cant wear- not that I really care about what people think. To be able to take a nice looking evening blazer, suit or whatever and stick in a street word if that is what I feel like doing and I would also wear it and let as many people see it as possible and of course, it is also part of my natural state of reinvention and always wanting to try new things and explore. So far, the reactions to the shows have been that people do have a need and a desire to see that kind of thing and I have realised that people want to be able to do that but out of fear, they can’t so they like the idea of seeing somebody else who does it and somebody else who has a meaning behind it and who is free and unafraid.

AD: If you had an aspiring artist who wanted to follow in your footsteps, what advice would you give them?

EA: I would certainly advise them to know their art history. I think it is really important that before you start developing your own style or working on your own concepts, that you know exactly where what you are doing is coming from, the people who have gone before you. I think that is super important. Because then you know where you are stepping and whether you are increasing something that somebody else has started or whether you are repeating. You don’t want to be doing that. You would obviously do that if you did not know what had come before.

I think they should find a way of making their work personal to them. Express yourself and create without trying to worry too much. I think there is no such thing as a wrong or right style of art. You really can come out with everything as long as you know you have some sort of meaning and backing to it. And I think its really important that its fun. Just try to make stuff that makes you feel alive. Its a bit like a comedian. Obviously, they don’t always get everything right but if a comedian comes out with a nice story that really is funny to them, I think there is a great possibility that it will be funny to most other people. So I think you have to definitely make sure you’re making stuff that excites you, or makes you laugh or makes you feel warm inside, that gives you that sense of yes, this is me. The moment you do that, I think you start to find your identity and I think the moment you have an identity then I think that other people will most certainly respond to you in a more real way. The thing about us artists as you well know is you can’t really hide what you feel and what you think because it shows in your work. So I think the moment they find their identity, it changes things. Because people respect that.

The last thing is to work hard. You have to work hard. Because it’s not a joke and it is harsh out there as you were saying earlier. And with the hard work, they shouldn’t over respect what has gone before. I think we should respect artists, we should respect different things that have been done. The way that we have shown work or the way artists have promoted themselves. But if you have other ideas in terms of how you can get your work out there or in terms of how you want to sell your work, whether you want to do it physically or through technology, just do it.

Blog: http://eugeneankomah.blogspot.co.uk/

Twitter: https://twitter.com/EugeneAnkomah

Fan page Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/pages/Eugene-Ankomah/62514151561